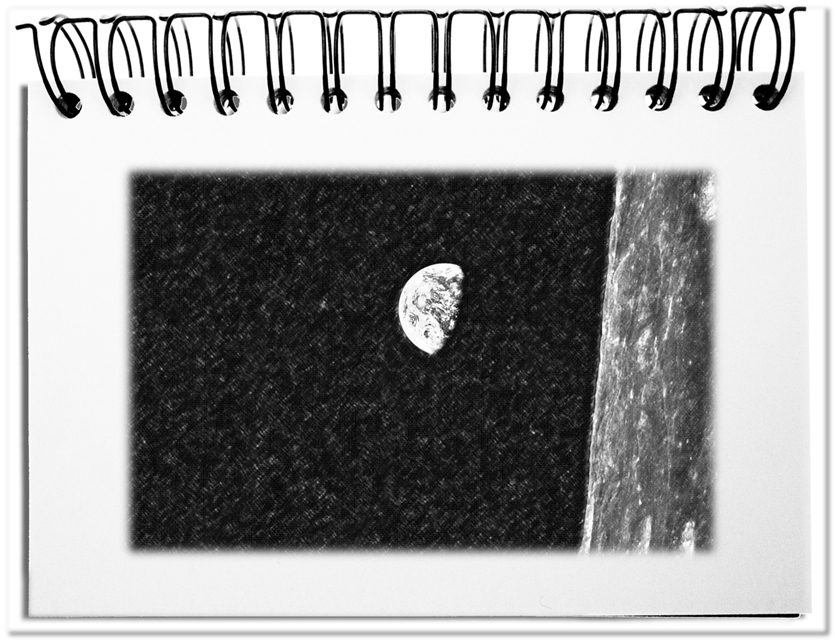

On 24 December 1968, a photograph, taken by William Anders while orbiting the moon with Apollo 8, changed its global identity. Through this unusual change of perspective, mankind was suddenly presented of how finite our lifeworld is. At the same time, computers made it possible to carry out simulations that facilitated the anticipation of the development of the world. The study The Limits to Growth appeared in 1972 and predicted that the absolute limits of growth in terms of world population, industrialization, environmental pollution and food production would be reached by 2072. At the same time, the Gaia hypothesis emerged, which sees the Earth as a self-regulating organism that resists its destruction when necessary. Regardless of what idea we have, we should be aware that we are on the only planet we can reach. Everything that happens here always happens to everyone sooner or later.

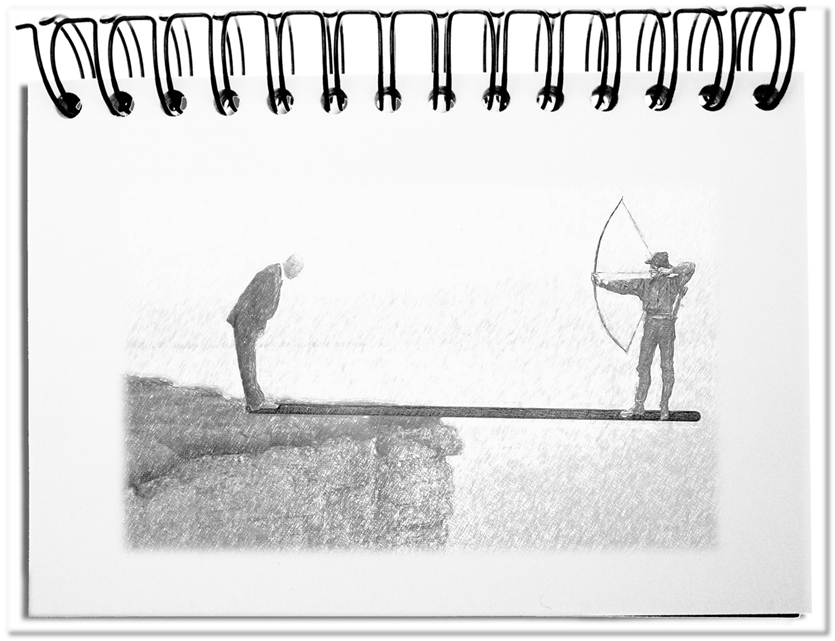

Given this interconnectedness, it is difficult to understand why some people still think they are not affected by the fundamental developments.

- Shared atmosphere

Without this air cover that surrounds the earth, there would be no life on earth. The interaction of fauna and flora is crucial for the 80% nitrogen and 20% oxygen. Natural chemical and physiological processes maintain the vital balance. Some people seem to think that the borders of their country also apply to the airspace and that they are not part of the problem.

The Earth, though, is a closed system in which, at first glance, problems are pushed from the left pocket into the right pocket – without realizing that you cannot get rid of the disadvantages. - Shared water

We have 1.4 billion cubic kilometers of water on earth – 97% salt water, less than 1% of fresh water in the groundwater and thereof just three thousandth in surface water. Life on Gaia depends on fresh water. Polluting this resource hurts everyone, also those contaminating.

To ensure that we will still have the quantities of fresh water we need tomorrow, we have to take care by ourselves, i.e. not to destroy this resource with nitrate from fertilizers, microplastics, oil, medicines and fracking for the benefit of a fistful of dollars. - Shared resources

We are sitting on finite resources – coal, oil and gas, copper, lead, gold and rare-earth elements. Without these materials we cannot maintain our current standard of living – food and water supplies, energy, mobility, as well as information and communication. The related estimates are limited to the deposits known to us. These are sufficient between 30 and two hundred years. After that, game over. - Shared destiny

The spaceship Earth is so large that it seems to us as if it were a flat disc. We are protected and kept alive by the atmosphere. Our vital supplies are what we produce on land and draw from the soil and the sea. That’s all there is. We consume more than twice as many raw materials nowadays, as we did fifty years ago. Every year, twelve million hectares of agricultural land gets lost through overgrazing, unsuitable cultivation methods, erosion as well as road and urban development. At the same time, the population will rise to nine billion people, who want to be supplied by 2050. Whatever happens on one side of the earth has an impact on the rest – without using the current, magic keyword.

Bottom line: The view of the rising earth has shown mankind how limited our scope of action is and will remain for a long time. There is only one atmosphere, shared water reservoirs and finite resources that make us ONE community of fate. Shifting resources from one side to the other harms the other side and adds nothing to the earth. Despite all the clues, influential people still haven’t understood the limits of growth, although they are also affected, because that’s all there is.

P.S.: At this point thanks to Greta.