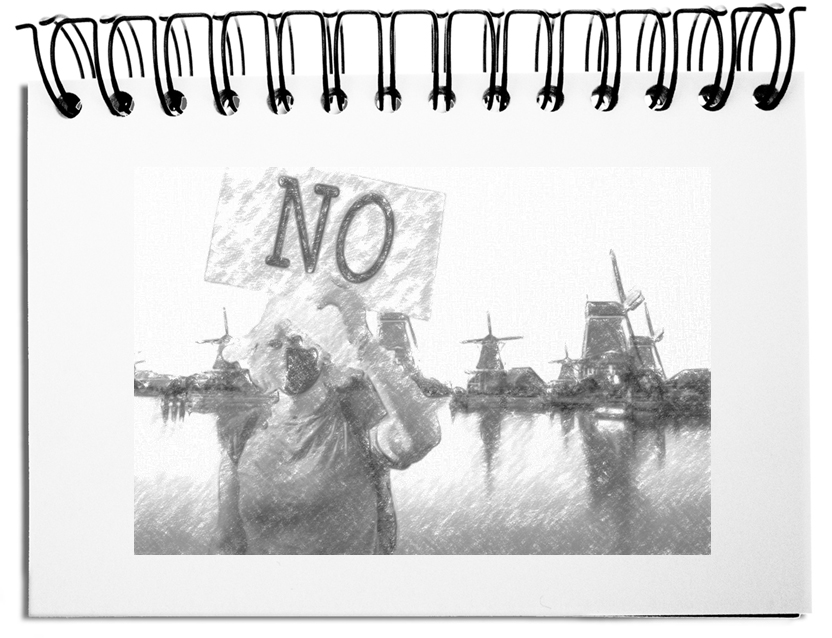

When decisions are made, in the slipstream swirl known and unknown consequences into advantages and disadvantages. Any measures that grant one-sided advantages to a few beneficiaries let cry out loud the self-appointed partisans from all corners of society. To what extent the disadvantages of the huge rotor blades of a wind power plant are more harmful than the MCA (Maximum Credible Accident) of a nuclear power plant seems to be in the eye of the beholder. Or is it more about the windmills that spoil the vista of some individual residents? People have been using windmills for over four thousand years. In the 16th century, there were documented 10,000 windmills in the Netherlands, and at the beginning of the twentieth century, over 18,000 in Prussia. Where would we be today, if the citizens at the time had opposed technological advances as the zealots of various faiths do today?

Current types of Luddites can be found in all age groups, political parties, and social classes. They got used to rate the world from their polarizing point of view. Usually, only the pros and cons of the desired outcomes are thought through. We need to neutrally expand the radius of our observation radar when making choices – regardless of the interests of the beneficiaries.

- Involve deciders in all impacts

Decisions lead to advantageous and disadvantageous consequences. If the decision-makers do not admit the disadvantages that arise, then criteria that have nothing to do with the matter move to the center. The bases of the decision change substantially if the deciders also go along with the burdening effects. - Consider all consequences

The most significant bias in decision-making is caused by a limited view of one’s advantages. In addition, recognized disadvantages are belittled. When assessing, the fading out of collateral consequences, in particular, distorts the broad perspective. Therefore, several scenarios must be developed that equally consider ALL opportunities and risks: the two sides of doing and not doing. - Charge the total costs of resistance

The follow-up costs of actions should be distributed among all those affected. This means that proponents AND opponents contribute to the charges. Depending on the on-site density of wind turbines, the price of electricity could be set as low as zero or multiplied if there is local resistance. It is up to everyone to decide whether to vaccinate. However, opponents of vaccination must expect disadvantages in the feared triage – to be relegated to the back of the queue according to the lack of contribution to society. With such burdens, the resisters receive additional criteria that they can consider in their resistance. - Decide independently of who shouts the loudest

Unfairly, those who shout the loudest tend to win the argument – self-absorbed politicians, demonstrators, and lobbyists. Fake news and propaganda create an additional flood of data that blurs the objective overview. Non-profit decisions should serve society, not personal interests. A typical example in politics is the intention to preserve jobs. With this argument, employees today receive lower pay, and what used to be mandatory employment is replaced by temporary contracts. Expanding precarious jobs leads to increased gains for corps and their functionaries – and politicians get their re-election sponsored. - For a common future with community spirit

When the results are no longer contaminated by personal motives, more objective and faster decision-making gets facilitated. For this, all participants need a sense of community that weighs the alternatives in the interest of the whole. The advantages and disadvantages of doing AND not doing and the indirect effects in adjacent areas must be considered.

Bottom line: The community benefits from results that generate advantages for society instead for a few. This is possible by considering all perspectives. Calculating the outcome as low as possible leads to delayed disadvantages. Furthermore, the effects of doing nothing and the pros and cons of the affected area must be considered. What surplus is created by the additional power sources of a new wind farm? What loss? What are the benefits of no wind parc? What are the cons? Which areas are additionally affected positively and negatively? No matter how you decide, those affected should be involved – directly or indirectly. Taking all effects into account reduces the follow-up costs. The individual parties pay their share of the total costs of their intentions in the way they gain. Deciding according to who shouts the most ignores relevant influences and reduces the intended benefit. Only with community spirit desirable prospects for all are open to society. Luddites who threaten this future must be held accountable for their acts. Angry citizens, opportunists, lobbyists, economic deciders, conspirators, and other ostracized extremists must bear the resulting costs of the unconsidered.